The last decades, astronomers have assumed that the Universe is expanding at the same rate in all directions. However, a new research, based on data from three X-ray space observatories, indicates that this fundamental assumption might be incorrect.

The idea that the Universe has the same properties in every direction, apart from some local irregularities, is based, among other things, on observations of the cosmic background radiation. This faint microwave radiation – a remnant of the Big Bang – is a reflection of the Universe when it was only 380,000 years old. And the fact that the cosmic background radiation is evenly distributed across the sky indicates that the Universe expanded in all directions at the same (high) rate in all directions.

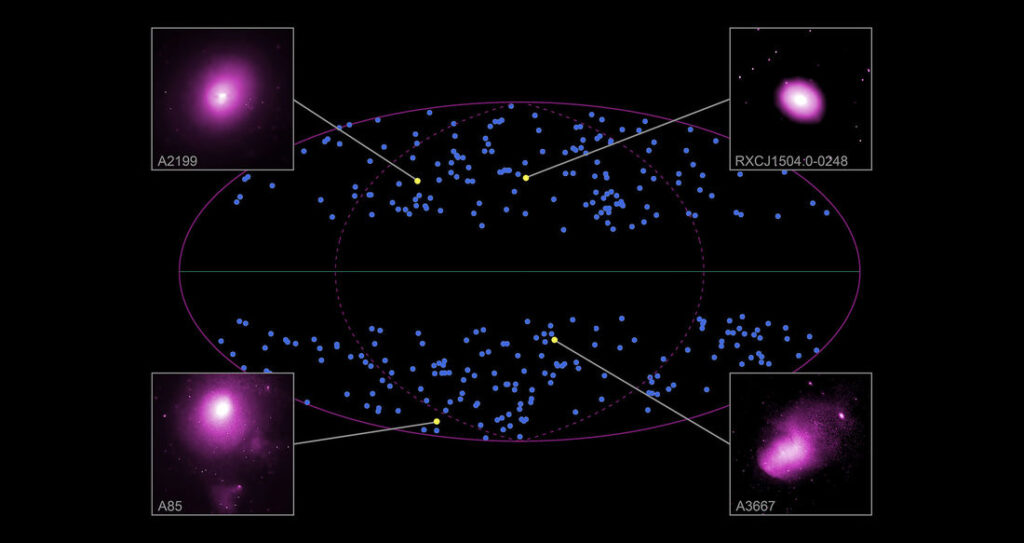

However, a team of astronomers from the University of Bonn (Germany) and Harvard University (USA), led by Konstantinos Migkas (Bonn), have now found evidence that the Universe is not as “isotropic” as it was thought. In particular, the astronomers examined 800 clusters of galaxies and found striking differences.

Based on data from the ESA’s XMM-Newton, NASA’s Chandra and the German-led ROSAT X-ray observatories, the temperature of the extremely hot gas in the space between the galaxies that make up the clusters has been determined. The results were then compared to how bright the clusters are in the sky. Clusters of the same temperature and at similar distances were expected to appear about as bright. But that turns out not to be the case: in one direction, comparable clusters seem up to 30 percent brighter than in the other.

In search of possible explanations, Migkas and his colleagues investigated whether the effect may be caused by gas or dust in the foreground or by irregularities in the spatial distribution of the clusters. However, no clear indications have been found for this. It seems that the Universe is not expanding evenly.

The astronomers suggest that the cause may lie in the dark energy, the mysterious cosmic constituent that represents almost seventy percent of all energy in the Universe. Little is known about this dark energy, except that it seems to have caused the Universe to expand rapidly over the past few billion years.

However, it is still a bit too early for far-reaching conclusions: the size of the sample that Migkas and his colleagues have taken is too small for that. So we are waiting for more data, which could be supplied by the European satellite Euclid, the launch of which is planned for 2022.

Euclid will measure large numbers of galaxies at distances up to 10 billion light-years to learn more about the distribution of matter in the Universe and the rate at which it is expanding. Also, the recently launched German-Russian X-ray satellite Spektr-RG, which is expected to detect tens of thousands of new clusters with the e-Rosita instrument, can also contribute to this issue.

Paper reference: Migkas, K., et al. “Probing cosmic isotropy with a new X-ray galaxy cluster sample through the LX? T scaling relation.” Astronomy & Astrophysics 636, A15 (2020).

Source: ESA, Chandra

Image on top: Cosmic expansion measured across the sky. Credit: K. Migkas et al. 2020 – CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO